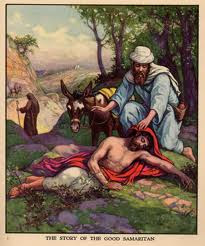

33 But a Samaritan traveller who came on him was moved with compassion when he saw him.

34 He went up to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring oil and wine on them. He then lifted him onto his own mount and took him to an inn and looked after him.

35 Next day, he took out two denarii and handed them to the innkeeper and said, "Look after him, and on my way back I will make good any extra expense you have."

There is much to learn from a careful study of the story of the Good Samaritan. You can look at the way Jesus made the members of his audience into the bad guys and a hated ethnic/religious minority into the good guys. Or why the religious people were the bad guys and the heretic the good guys. Or why Jesus, in telling this story, ignored the question he pretended to be answering. He didn’t, as we say today, “buy the premise” of the question. There is, of course, a premise underlying the answer, and we would be justified in wondering whether the lawyer who asked the question noticed that there was another premise available to him and switched over to it.

This post is not about any of those things and it is “about” the Good Samaritan only as a jumping off point. The question I would like to explore today has bothered me for some time. I suspect that is because there is no good answer to it. Here are three stories about the situation the Samaritan encountered.

Story I A Samaritan traveler came upon a victim of highway violence and, although he himself was vulnerable to the same threat, he had an emotional reaction toward the victim and stopped to help him. He administered first aid and took the victim to an inn where he gave instructions that the victim was to be cared for and that he, himself, would pay whatever it cost.

The victim was lucky, in a sense, because travelers didn’t come up that road all the time and not all who came would have stopped to help him. There are some very good reasons for not stopping, simple prudence among them. So even though the victim’s life was saved through the happenstance of a willing helper coming along before it was too late, we call it an uplifting story and name hospitals after the benefactor.

Story II Several versions of the story Jesus told circulated in Jerusalem and Benjamin, who knew the innkeeper, heard one of them and started thinking about it. Benjamin wasn’t a particularly sympathetic person and was not in any way a politically engaged person, but he was gregarious and well-known and well-liked. And while his innkeeper friend had an uplifting story to tell about the satisfactory recovery of his guest and the more than satisfactory profit he had made, Benjamin kept thinking that all the good of this story was just happenstance. What if no one had come along? What if the person who did come along just kept moving?

So Benjamin started talking to his friends at the Jerusalem Chamber of Commerce who had friends at the Jericho Chamber of Commerce and they came up with a plan to take some of the happenstance out of this trip. Could encourage tourism too, you never know. The plan involved the regular deployment of groups of five at hourly intervals, starting simultaneously from Jerusalem and from Jericho. Five was a big enough group to deter bandits and one of them would be armed, in any case. All were trained in first aid and carried packs containing oil and wine, with a total value of two denarii.

You can’t stop bandits from preying on travelers, certainly, but the regular provision of medical care and transportation is something that can be done. There is an organizational burden to it, of course, and finding enough volunteers is always a hassle, but Benjamin’s plan leaves everyone better off except the bandits. And, really, who cares about the bandits?

Story III. Simeon heard about Benjamin’s rescue brigades and rolled his eyes. He had been asked to serve on one of the teams and turned it down. He was polite to Benjamin, but that evening he quipped to his wife that the brigands were doing more for economic development than the brigades were. He liked that. It kept running through his mind and eventually it stopped running and just sat down. “Why spend all this time patching up victims when the brigands are just as much victims as the travelers? Has anyone given any thought to what kind of life this must be for them? Surely they wouldn’t choose such a life unless nothing else was possible for them.”

Simeon didn’t have any of the Samaritan’s compassion and not very much of Benjamin’s networking skills, but he did know some people in the unfortunately named Jerusalem Economic Redevelopment Commission. JERC had had some success in getting Empire Redevelopment Grants (ERGs) from Rome and would be open to a new idea.

The first grant enabled economic development planning for the area surrounding the route from Jericho up to Jerusalem. They were lucky on the third try. There was not enough rainfall for the proposed barley farms. There was not enough foot traffic for the proposed water slide. But there was a good deal of silver ore in the mountains. The subsequent grant enabled the establishment of several highly profitable silver mines, which were turned over to the former brigands on the condition that there were to be no more “accidents” happening to travelers.

The outcome pleased everyone. The authorities in Rome were delighted to have ended a source of public disorder in a notoriously volatile part of the empire and to have a source of silver for the denarius coins. The bandits were happy to exchange their marginal and violent life for a stable and prosperous one as prospectors, miners, and dealers in precious metals. The travelers were not pleased because they immediately forgot how dangerous the road was, but they benefitted nonetheless. Simeon was acclaimed by his peers and enriched by his share of the new silver profits—just the merest sliver of the profits; almost as low as a finder’s fee. Simeon’s wife was pleased because Simeon finally stopped telling the “brigands and brigades” story at parties.

True Religion and Undefiled

True religion and undefiled is to feel compassion for the widows and orphans as they are evicted from their homes to make way for an eight-lane expressway. James 1:27, Hess paraphrase.

These three stories make an odd pattern when you consider them together. The “best person” is without question, the Samaritan. He saw, bloody beside the road, not a hated enemy, but a wounded fellow traveler. He was “moved with compassion” and acted on his feelings with prompt, courageous, and generous action. Benjamin’s idea that there was no trusting of happenstance compassion and also no need to, is not all that praiseworthy. Simeon’s idea that he could get an ERG and change the economic climate of eastern Judea was insightful, but not otherwise meritorious.

If you consider this to be a story about compassion, you would rank the characters: 1. The Samaritan. 2. Benjamin. 3. Simeon.

If you consider this to be a story about improving life for everyone, there is no question that you would get: 1. Simeon. 2. Benjamin. 3. The Samaritan. The Samaritan saved the life of one traveler. Benjamin saved the lives of countless travelers. Simeon saved not only the travelers, but the brigands as well.

Theoretically, there is no reason all three characters can’t have all three traits. All three characters have the compassion of the Samaritan, the social skills of the networker, and the economic vision of the developer. Theoretically. Practically, we find that different people have different gifts and that not every economic developer has the compassion of a trauma nurse. That means that most of the time, we will have to choose one approach or another; we will have to valorize one kind of person or another. We will have to rank people by the good they did or by the acted upon feelings they had.

WWJD?

Jesus told his story to frazzle the lawyer. It’s a motive we can all understand. If Jesus were to make a choice among our three characters, there is no question in my mind that he would choose the Samaritan. And that’s the principal thing wrong with WWJD. The question any Christian of our time would want to ask is WWJHMD—what would Jesus have me do? The first thing, obviously, would be to buy a bigger bracelet. But after that, would Jesus—now our adviser, not an itinerant rabbi—want to begin with compassion? Would he say that actions that don’t begin with compassion are unworthy of his followers? Would he say that what Benjamin chose to do is a good thing IF and only IF is began with feelings of compassion on Benjamin’s part?

I hope not. I can imagine myself feeling compassion for a traveler. It is harder to imagine my compassion upon hearing a story about a guy with so little road smarts that he got himself involved in a nasty incident on the road from Jericho. If following Jesus means beginning with compassion, the travelers are the only ones playing the game.

Or would Jesus—the adviser, again, not the teacher—say that providing for the needs of hundreds of travelers is better than providing for the needs of one? Would he single out for special praise the people who have the ideas that benefit many people, even if their emotions were not engaged? Would he consider the hassle of maintaining the network of volunteers to be “faithful service,” or just a nice thing to do? Sweet, but secular. I can tell you that Jesus’ body, his church, is going to have access to the services it values. Services it needs but does not value are going to be outsourced and purchased. You can’t purchase compassion at all, but purchasing networking and volunteer maintenance is surprisingly expensive and all that money comes from the evangelism fund.

Or would Jesus take compassion on the brigands, and in that compassion, praise Simeon? Simeon doesn’t have any people skills at all, but he has vision and he has Imperial contacts. There are a lot of things he could have done that didn’t help anyone on that road—either the travelers or the perpetrators of violence. What he chose to do benefitted everyone and Simeon might be a religious man or not; emotionally engaged with his fellowmen or not. Would Jesus say that the mark of Simeon as a follower of his can be seen in his care for his wife and children, not with his use of his business contacts?

Valuing only compassion is like valuing only a sugar high. And then what?

Here is a comment my friend Bonnie Klein wanted to post and ran, somehow, up against the Google Border Guard.

ReplyDeleteI think one of the keys to the answer you’re looking for is in the idea of “benefit.” There is some QUALITY of the benefit rendered by each main character that is substantially the same. Whether one made money from providing the benefit or not, whether one’s motive was compassion or not, the results of all three characters’ actions answer Jesus’ command to care for the downtrodden.

Now, I’m not saying any action that results in benefits qualifies as following Jesus’ command, but as you have written it here, none of these men did what they did strictly for themselves or at others’ expense, the way people say Exxon’s billions in quarterly profits are made on the backs of the Average Joe at the tanks. While Simeon may not have felt compassion, what is it that made him see a vision that would benefit everyone, instead of one that would benefit only himself? That thinking-outside-oneself / thinking-for-the-benefit-of-others, in my mind, qualifies as a type of compassion.

And, might James 1:27 have been written for a particularly hard-hearted church? I mean, we recognize that people have widely varying cognitive abilities, that physical ability differs from person to person, why do we expect everyone to experience the same emotions to the same degrees? Jesus doesn’t require that we are of a certain intelligence or physical capability to follow him. Why would His “compassion requirement” be different? Seeking to “make things better for others,” whether motivated by a deep compassion or a nearly untraceable one, is the focus, I think, of both Luke and James, and that leaves out people who hurt, use, or impoverish some to help others.

All that said, one word at the end of your post bothers me a little. And it’s a word that brings up the other key to your answer: “religious.” Simeon has no people skills, is not emotionally engaged with his fellowmen, ok. All that is consistent with the points in your post. But Simeon is also described as possibly not being religious. Does that mean he does not behave “religiously,” does not do the things “religious” people do? Or does it mean he doesn’t “religiously” try to follow Jesus? One can do good deeds all day long, but if he is not going to “follow Jesus,” how can he be a Follower of Jesus, and, so, how can this command even apply to him? It is CHRISTIANS, whether they are thin on compassion or not, who act in ANY of the ways the Samaritan, Benjamin, OR Simeon acted that seem to me to meet Christ’s requirement.

Sometimes, I think, we conceive of ourselves as being so different from other Christians that we can become unable to recognize how we fit into the Christian community, so different that perhaps we wonder whether we are being “Christian” at all.

From the cleverness of “brigands to brigades” and “It kept running through his mind and eventually it stopped running and sat down,” to the focus on the great diversity of Christian persons within the Christian community--this was a wonderful post, Dale. Thanks.

Bonnie